Spotlight Archive

During this Lenten season, adults who have decided to enter the Catholic Church spend their final weeks of preparation before baptism and profession of faith at the Easter Vigil Mass. In the midst of a religiously pluralist nation, they join a remarkable line of Catholic converts who have contributed immensely to the life the American church.

Long before the birth of the United States, French missionaries labored in upper New England and the Great Lakes region. One of their converts was a young Mohawk woman later beatified by the Church, Kateri Tekakwitha. In the English colonies of the eastern seaboard, Catholics were a tiny minority, reaching only one percent of the population by the time of the Revolution. Forming communities of any size only in Pennsylvania and Maryland, colonial and revolutionary-era Catholics tried to get along with their Protestant neighbors—culturally and ethnically, at least, they mirrored the English and Scots-Irish population that dominated the young nation.

Even so, it was a large step for an American to elect to transfer his or her religious allegiance to Roman Catholicism, and therefore especially remarkable when it occurred. In New England, where Catholicism had been strongly proscribed, it was doubly so. Yale alumnus John Thayer was one of the first cases. Converted in Europe, he became a priest before returning to his native Boston. The Barber family of New Hampshire converted in the 1810s—first son Virgil and his wife, then mother Chloe and her other children, and finally father Daniel. Daniel and Virgil had both been Episcopalian ministers, the latter in charge of one of that denomination’s academies. Virgil and his wife, Jerusha, moreover, determined to part ways and join consecrated life, he as a Jesuit and she as Visitation nun.

Another family affair was the Floyd conversion of the 1830s, set in motion by daughter Letitia. Her father was the governor of Virginia at the time, and so her embrace of Catholicism caused a sensation in the Old Dominion. She was followed into the Church by two sisters (one a senator’s wife), three brothers, and, finally, her father and mother.

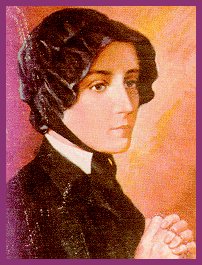

Perhaps the most notable convert of the early years of the nation was New York matron Elizabeth Ann Seton, who joined the Church four years after the death of her husband in 1801. She founded the American congregation of the Sisters of Charity and applied her efforts to the foundation of Catholic schools in the United States. Seton’s first school was in Baltimore, whose fifth bishop was also an early nineteenth-century convert, Samuel Eccleston. The eighth bishop in that see’s line of succession was James Roosevelt Bayley, nephew of Saint Anne and an 1842 convert from the Episcopal ministry. Bayley was one of several 1840s bishop-converts: there were also Edgar Wadhams (Ogdenburg); Richard Gilmor (Cleveland); James Wood (Philadelphia); and Thomas Becker (Wilmington).

Perhaps the most notable convert of the early years of the nation was New York matron Elizabeth Ann Seton, who joined the Church four years after the death of her husband in 1801. She founded the American congregation of the Sisters of Charity and applied her efforts to the foundation of Catholic schools in the United States. Seton’s first school was in Baltimore, whose fifth bishop was also an early nineteenth-century convert, Samuel Eccleston. The eighth bishop in that see’s line of succession was James Roosevelt Bayley, nephew of Saint Anne and an 1842 convert from the Episcopal ministry. Bayley was one of several 1840s bishop-converts: there were also Edgar Wadhams (Ogdenburg); Richard Gilmor (Cleveland); James Wood (Philadelphia); and Thomas Becker (Wilmington).

The complexion of the Church in the United States changed as immigration increased over the course of the nineteenth century, with millions of Catholics entering the nation from Ireland and Germany, from eastern and southern Europe, and from French-speaking Canada. Even as Catholics became an increasingly large portion of the American population, their status as ethnically and linguistically “other” made conversion for many Americans a controversial enterprise.

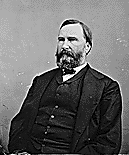

Yet converts were among the foundation-layers of the nineteenth-century church. Social activist Isaac Hecker rejected his introductions to Lutheran, Calvinist, and Transcendentalist faiths before finding a suitable home in Catholicism in 1844. After a period in the Redemptorist order, he formed a new American society of priests, the Paulists (among whose early number were other converts, such as Francis Baker.) Hecker’s correspondent and fellow Transcendentalist Orestes Brownson became the most celebrated convert of the period. Brownson was already well known as a religious leader, philosopher, and publisher when he entered the Catholic Church in the same year as Hecker. In a period when the Church lacked intellectual respectability, Brownson promoted Catholic views to an educated public through his many essays in Catholic and secular publications. One of the polemical Brownson’s literary opponents was New York publisher James McMaster, the convert son of a Presbyterian minister.

Yet converts were among the foundation-layers of the nineteenth-century church. Social activist Isaac Hecker rejected his introductions to Lutheran, Calvinist, and Transcendentalist faiths before finding a suitable home in Catholicism in 1844. After a period in the Redemptorist order, he formed a new American society of priests, the Paulists (among whose early number were other converts, such as Francis Baker.) Hecker’s correspondent and fellow Transcendentalist Orestes Brownson became the most celebrated convert of the period. Brownson was already well known as a religious leader, philosopher, and publisher when he entered the Catholic Church in the same year as Hecker. In a period when the Church lacked intellectual respectability, Brownson promoted Catholic views to an educated public through his many essays in Catholic and secular publications. One of the polemical Brownson’s literary opponents was New York publisher James McMaster, the convert son of a Presbyterian minister.

The mid-nineteenth century was the era of American expansion, and Catholic convert John McLoughlin played a major role, laying the groundwork for the state of Oregon as head of the Hudson Bay Company. It was also the era of John Henry Newman’s celebrated Oxford Movement, which had its impact on this side of the Atlantic as well. Levi Ives was a bishop in the Episcopal church of North Carolina when he became convinced of Catholic claims. He entered the Church as a layman in 1852.

Catholics fought with distinction on both sides of the Civil War, and Catholic converts emerged from both militaries. Union brigadier general John Gray Foster professed the faith in 1861. Confederate general James Longstreet settled in New Orleans after the war and joined the Church in 1877.

Catholics fought with distinction on both sides of the Civil War, and Catholic converts emerged from both militaries. Union brigadier general John Gray Foster professed the faith in 1861. Confederate general James Longstreet settled in New Orleans after the war and joined the Church in 1877.

Orestes Brownson was but one in a string of literary converts. Light fiction writer Anne Dorsey became Catholic in 1840. Mary Agnes Tincker, a popular novelist of the 1870s and eighties, had converted in 1853. Southern writer Joel Chandler Harris accepted the faith at his death in 1908. The twentieth-century South produced writer-converts Allen Tate, Caroline Gordon, and Walker Percy.

Brownson was also one of a number of prominent intellectuals to "cross the Tiber." Others included Ivy League historians Carlton J.H. Hayes and Christopher Dawson; conservative scribes Willmoore Kendall and Russell Kirk; and philosophers Jacques Maritain and Dietrich von Hildebrand.

Thomas Merton wrote about his conversion story, thereby penning a twentieth-century spiritual classic. He published Seven Story Mountain in 1948, ten years after his conversion and seven years after entering the Trappist monastery of Gethsemani, Kentucky. Another interwar convert, Dorothy Day, became an influential laywoman, most notably by founding the Catholic Worker movement. Knute Rockne, legendary Notre Dame football coach, also entered the Church in the 1920s.

Thomas Merton wrote about his conversion story, thereby penning a twentieth-century spiritual classic. He published Seven Story Mountain in 1948, ten years after his conversion and seven years after entering the Trappist monastery of Gethsemani, Kentucky. Another interwar convert, Dorothy Day, became an influential laywoman, most notably by founding the Catholic Worker movement. Knute Rockne, legendary Notre Dame football coach, also entered the Church in the 1920s.

Catholic conversion thrived in a post-World War II era in which second and third generation Catholics enjoyed new levels prosperity and respectability. Avery Dulles, son of secretary of state John Foster Dulles, joined the Church while at Harvard in the 1940s. He became a well known theologian and was made a cardinal in 2001. Bishop Fulton Sheen ushered a number of famous converts into the Church, including Clare Boothe Luce and Henry Ford, Jr. Ford’s case indicated that the conversion process did not always have a storybook ending: he stopped practicing his faith after his Catholic marriage dissolved.

Catholic conversion thrived in a post-World War II era in which second and third generation Catholics enjoyed new levels prosperity and respectability. Avery Dulles, son of secretary of state John Foster Dulles, joined the Church while at Harvard in the 1940s. He became a well known theologian and was made a cardinal in 2001. Bishop Fulton Sheen ushered a number of famous converts into the Church, including Clare Boothe Luce and Henry Ford, Jr. Ford’s case indicated that the conversion process did not always have a storybook ending: he stopped practicing his faith after his Catholic marriage dissolved.

Hollywood produced its share of converts. Gary Cooper joined the Church in 1958. Jane Wyman, first wife of actor and future president Ronald Reagan, was a convert and third order Dominican. Dolores Hart converted as a child, and ended her acting career at age 24 by entering a Connecticut convent in 1963. John Wayne became Catholic shortly before his death in 1979.

In the late twentieth century, converts continued to maintain high profiles in the Church. Dulles was a towering figure in American theology, while Richard John Neuhaus, a Lutheran minister who embraced Catholicism in 1990, was one of the most prominent Catholic public intellectual in the United States until his death in early 2009.

Late-century converts were a shrinking group. Statistics show that the phenomenon of Catholic conversion declined in percentage terms after 1950. There were 4.3 converts per 1,000 Catholics in that year, 2.1 in 1969, and 1.6 in 1979. Intermarriage (Catholic marrying non-Catholic) and Catholic schooling were key “sources” of converts throughout the period. Although the absolute numbers of students in Catholic schools declined over the period, both the percentage of non-Catholic students and the rates of intermarriage increased.

Beneath the numbers and trends, however, are individual stories of growth, faith, and conversion, each one personal and unique. As long as the Church endures and people search for truth and meaning, conversions will occur, and converts will remain a vital part of the life of Catholicism in America.

Note: Not every convert listed above was born in the United States. If not, they were included because they converted while in the U.S. and/or spent a significant number of years living there.

©2009 CatholicHistory.net. Posted March 16, 2009.

Photos, from top: Elizabeth Ann Seton; Orestes Brownson; James Longstreet, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted); Dorothy Day, courtesy of the Marquette University Archives, Milwaukee Journal, 1968; Clare Boothe Luce, courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (unrestricted).

Sources and Further Reading

T. Shelley, "American Catholics: 1815–1865,"